Muscle strains, like tendonitis, are one of the more pesky injuries to deal with because they decrease the ability to train and practice the sport effectively. Sadly, strains can be one of the injury conditions that is problematic to rehabilitate because of the preponderance to re-strain the muscle again during athletic activity.

Table of Contents

- Strain etiology, assessment, and grading

- Rehabilitation — Acute/Inflammator Phase

- Rehabilitation — Repair and Remodeling Phase

- Conclusion

Strain etiology, assessment, and grading

Strains, pulls, tears, and ruptures are different names that describe the same muscle injury—the only difference is in the degree of injury sustained. A strain or pull is less serious than a tear or rupture. To keep it simple, the term strains will be used from this point forward.

Etiology and Assessment

A muscle strain occurs when the amount of force put on a muscle is greater than the ability of the muscle to generate an opposing force. This most often occurs during high-speed movement, however, it can also occur during sustained contractions. It tends to happen near the end of workouts when muscles are fatigued and cannot generate as much force as they could in the beginning of a workout. Muscle strains have a higher frequency of occurring under these circumstances:

- Where there has been a previous strain, because of an existing muscle weakness.

- After static stretching, as you begin to move into athletic activity, because the desensitization of

muscle spindles may contribute to a muscle lengthening much farther than it should. - In older populations, because the muscles become less pliable with age.

- In muscles with poor flexibility and mobility, because the muscle cannot elongate very far without

straining especially as you fatigue. - Near the end of workouts, because muscles have less ability to maintain adequate force output to prevent straining as fatigue increases.

- In weak people, because weak muscles strain more easily.

- In impingement—when the motor nerve output is decreased it leads to a decrease in force production from the muscle.

Muscle damage—especially factors related to the damage like delayed onset muscle soreness—is caused by eccentric muscle contraction. The same thing occurs with strains. They occur during the eccentric contraction of the muscle. Even in cases where a strain appears to occur during a ‘concentric’ contraction, it is actually happening during an eccentric contraction (right at the time of transition) or when the force is too great and tears the muscle.

The vast majority of strains—aside from catastrophic strains—will occur during an eccentric movement. Hamstring strains occur when the knee is moving forward or the foot is receiving the ground as the hamstring is lengthening. Back strains occur during deadlifts, as the back is rounding and the spinal erectors are lengthening. Biceps or shoulder strains occur when coming down from the top of a pull-up. In kicking sports, strains will tend to occur after kicking the ball extremely hard, as the leg travels up and forward in front.

Knowing the factors that increase propensity for strains is important. If you are more prone to strains, you must use caution when operating at high intensities. Athletes with known medical issues or previous strains need to be proactive. When performing intense workouts at high speeds, be sure to warm-up adequately and save the static stretching for after the workout. The one exception is if there are flexibility issues that impair proper technique. These should be addressed prior to working out to ensure safety during a workout. If you are doing intense workouts at high speeds, save the static stretching for afterwards unless you have flexibility detriments that need to be addressed prior to workouts to ensure safety during the workout. You can find more about the the when and why of static stretching in this previous published article.

When a strain does occur, here are a few signs that will help you recognize what is happening:

- There is pain in muscle lengthening and in muscle contraction.

- Strains tend to occur with a sudden and sharp onset of pain.

- Strains tend to occur in the muscle belly, the soft tissue of the muscle

- If the strain is severe, swelling and/or bruising may occur.

- If the strain is a tear, a divot or gap may appear in the muscle or it may rend apart altogether.

Strains are graded on a one to three scale:

Grade I tears consist of minor muscle tearing. There is little to no swelling and no bruising, but pain is present in the soft tissue. The amount of pain is often variable and contingent upon how the person perceives it. It is possible that pain will only occur during eccentric movements and not concentric movements. When light pressure is applied to the strained area, it is unlikely that you will feel intense pain, but you may feel a level of discomfort or mild pain.

Grade II tears are partial tears of the muscle. There is likely to be some swelling. Bruising is variable but will most likely be present, as the tissues are damaged/ruptured enough that there will be blood leaking out. Both concentric and eccentric movements will hurt, and putting pressure on the area will cause pain. You will have limited range of motion in the injured muscle and it will often begin to get tight in order to protect the injured tissues.

Grade III tears are complete or near-complete ruptures of the muscle. There will be swelling and bruising. There is likely to be a divot or gap where the muscle is torn apart. If this occurs, it is important to use compression and seek immediate medical attention. In the event of a Grade III tear, go directly to the emergency room. (It is advisable to do so in the event of a Grade II tear as well; however, it may not be necessary in all cases. In any event, the following information is directed to those with Grade I and low Grade II tears only.)

Rehabilitation — Acute/Inflammatory Phase

Strains are different from tendonitis. With a strain, an actual injury has occurred, whereas an overuse injury like tendonitis may manifest as soreness or discomfort without any tissue disruption taking place. Prehabilitation for a strain will begin in the tissue remodeling phases rather than skipping to specific prehabilitation of the area.

If you are weak, you need to get stronger. If you have very tight muscles, it is imperative to increase mobility in those muscles through static stretching and/or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitative stretching after your workouts. If you are older, it is essential to properly warm up before every workout, and you should perform all of your static stretching after your workouts unless your body requires it to help maintain proper technique.

Most importantly, always maintain proper technique. If you are performing timed workouts, it is important to emphasize technique over hitting a faster time. Constantly drilling technique is the key to success in every sport and athletic endeavor. You are not doing yourself any favors by taking shortcuts to look or feel better, you only increase your chance of injury when you do so.

The acute phase in all injuries is characterized by tissue damage that elicits an inflammatory response in the muscle. Swelling and bruising may or may not be present; however, if either is present, it is critical that you take all of the proper steps to encourage tissue healing:

- Use Heat: You can do this immediately if there is no swelling. Blood flow to the area is beneficial.

There is some controversy over going directly to heat for acute injuries, so ice can be used if you

want to stick to standard protocol. If there is swelling, you should use compression. - Anti-inflammatories: Talk to your doctor first. For Grade I and II strains, most doctors will give

you a prescription for NSAIDs like ibuprofen. Follow your doctor’s guidelines. Be aware that

chronic use of NSAIDs can lead to stomach issues. - Keep Moving Without Causing Pain: It is important to keep the body part mobile in order to

keep the muscles from tightening up and inhibiting the nervous system sensitization from the pain. Do not move in a way that causes pain. Strains should never be stretched because that is typically how they were injured in the first place. - Self-massage: If there is excessive swelling, use your hands to push the swelling up toward your

heart. This will help clear it out and speed up the healing process. Self-massage in this phase

should focus on light/superficial massage to the surface of the skin that moves swelling toward the heart. Do not push hard into the tissue roughly.

In general, these phases are aimed at mitigating the body’s response to injury by tightening up the muscles and being more protective. This tends to lead toward tight, contracted muscles which need a longer time to rehabilitate in order to get back toward athletic activity. This phase usually lasts a few day in minor injuries up to a week or two in larger injuries.

Rehabilitation — Repair and Remodeling Phase

These phases are usually separated, but repair and remodeling can occur simultaneously if the muscle is cared for properly.

In this stage, the body is repairing the damage that can be repaired, breaking down what cannot be

repaired, forming scar tissue, and laying down new tissues. This phase begins within 48-96 hours after injury.

When swelling is reduced and the tissue begins to feel better in movement, consider that you have left the acute phase and entered this phase. Be conservative in your judgment so as not to reinjure the strain, and take the following steps:

- Continue Using Heat: This helps increase blood flow, loosens tight muscles, and allows for

increased movement capabilities. Keep moving as much as you can without pain. - Continue Anti-inflammatories: Use as needed for both pain and excessive inflammation. (Always consult a doctor before using any medications.)

- Maintain Self-massage: See above section for details.

- Add Mobility Work: Shift your primary focus to loosening tight muscles. You can massage

deeper, provided that you are not inflicting pain. Add mobility work after to help expand your range of motion. It is best to stretch into the range of discomfort but stop short of pain, as this

can aggravate the injury. All of this is in addition to frequently moving the affected area.

Programming in this phase may follow these steps:

- Apply heat to the affected muscle (10-15 minutes)

- Massage the affected muscle (10-15 minutes)

- Perform mobility work focused on maintaining and slightly improving range of motion (5-10

minutes).

Along with the repair and remodeling phases is also when you will begin to resume exercises.

Resuming Exercise: Like with tendonitis, begin with very light weights so you have a good degree of

control over the movement, which will ensure that you do not re-strain the muscle. Take it very slow: it is very easy to aggravate the affected areas.

Perform isolation work if it can be done without aggravation of the affected muscles. Keep the weight very low and only perform a few sets of 15-25 repetitions per set. Aim for a tempo around 5121 (similar to what you would use for tendonitis) that focuses on slower eccentrics, controlled concentrics, and pauses. Now is not the time to be aggressive with weight increases. If there is any type of twinge in the muscle, back off immediately. You want to work higher repetitions to build endurance, as your tissues will be extremely vulnerable when fatigued. With any injury that cannot be isolated (such as a lower back strain), supplement with isometrics. Non-weighted squats, back extensions, or very light deadlifts/good mornings can work well. For back strains, reverse hyperextensions can help, but use caution.

In most cases, you can perform isolation work nearly every day of the week provided that you keep the exercise low intensity and you feel better the next day. Keep the exercise and movement high, without fast progression. Use extra caution; it will take you even more time to recover if you re-strain a muscle.

Slowly progress your way from isometric exercises by increasing intensity. Once you have strengthened the area sufficiently, work your way back to light compound exercises. From there, progress the intensity in your compound exercises. At this point, you will be on your way back to full workouts. Progress will vary based on the individual. Don’t be afraid to take it slow, as a re-injury will cost you significantly more time and anguish.

For more experienced lifters Bill Starr’s method of rehabilitation may be effective as well.

Preventative Measures: As discussed, strains are more likely to occur if you have strained a muscle previously. Here are a few things you can do to prevent another strain.

Improving mobility and flexibility is a major factor. This work should be integrated into your warm-up and cool down. Add in some soft tissue work like foam rolling and/or self-massage. Do dynamic and static stretches when appropriate.

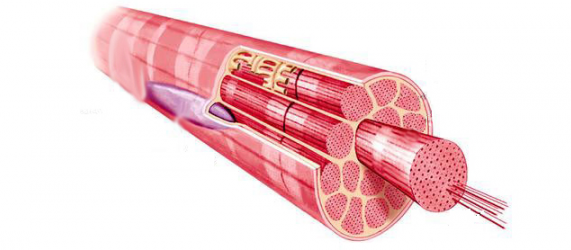

Next, make your muscles more resistant to damage. As you know, the majority of damage that occurs during exercise takes place while performing eccentric movements. However, the muscles themselves gain a resistance to damage with repetitive eccentric work. The model by which this occurs is the popping sarcomere theory. This theory states that, during eccentric exercise, individual sarcomeres distend while a muscle is being lengthened, which accrues as damage. Excess or macroscopic sarcomeric distension in a localized area is a strain, but the body responds to microdamage by adding additional sarcomeres to the muscle during the inflammatory phase of the healing process. Subsequently, the muscle becomes more resistant to damage.

This means that the bulk of prehabilitative work should focus on slow, eccentric exercise. This is especially true if your routine or sport requires explosive movements. For example, a sprinter with a hamstring or groin strain will want to focus on eccentric hamstring curls for a 6-10s negative phase with higher repetitions. This will enable the athlete to build up resistance to damage in the future while rehabilitating the injured muscle(s) back to full strength.

You can then progress in your prehabilitative work to a 6-10s eccentric on the eccentric portion of com pound lifts like deadlifts, good mornings, hyperextensions, Romanian deadlifts, and similar exercises. The goal is to work back to this type of strength and power work before resuming explosive exercises if your goals require them. Do not be too aggressive in adding weight and take care to strictly maintain your technique.

Hamstring rehab example

Some specific muscle strains such as Hamstrings have very specific tests that can be used to rehab:

https://www.physio-pedia.com/Askling_Protocol

They also have a test that is used before return to sprinting to ensure that the hamstring is strong enough:

Supplements: Generally speaking, for the recovery process for a muscle strain enough protein is needed. If you are not getting enough protein through your diet as recommended for athletes — 0.7 grams/lbs a day — then you may want to supplement to get enough. 0.7-1 g/lbs per day is a good target to aim for. ON Whey is solid.

Fish oil may be beneficial, although there are no studies to confirm. Generally speaking, most of us have some markers of chronic inflammation due to excessive stress from lack of sleep, poor nutrition, little to no exercise (especially now with an injury), and chronic stress from a job or family. Fish oil can bring whole body systemic anti-inflammatory effects, especially since the body cannot heal properly if there is too much excessive inflammation. The goal is to limit inflammation from being excessive, since some inflammation is needed to heal the particular injury. Carlson’s fish oil is one I have used before. High DHA/EPA content. Doesn’t taste nasty. Generally, aim for 2-5g per day.

Conclusion

It is not difficult to recover from Grade I and low Grade II strains. High Grade II strains may require

more attention. Treat them with the same methods, just know that the acute, repair and remodeling phases will take much longer. If you have a Grade III strain, you need to be seen by a qualified medical professional.

If you have a muscle strain, the hard part is having the patience to take care of your body through the protocols mentioned above. Be disciplined. Do not take your body for granted. Think of this time as a learning experience that you do not want to repeat. Perform proper mobility work, prehabilitative work, rehabilitative work, and focus on maintaining proper technique. Go slow.

Note: there are specific guides out there now that are useful. This one provides a lot of athletic eccentric exercises to get your hamstrings back ready for sprinting, as the hamstring is one of the most often strained muscles during athletic activities.

This article was originally published January 15, 2010 on Eat Move Improve. Updated Feb 2024.

Questions about articles may be addressed to the Overcoming Gravity reddit.

Disclaimer: Any information contained on this site should not be misconstrued as professional medical advice. Always consult your appropriate medical professional before using such information. Use of any information is at your own risk.

I may earn a small commission for my endorsement, recommendation, testimonial, and/or link to any products or services from this website. Your purchase helps support my work on education on health and fitness. See also: Full disclosure of site terms and conditions.

Author: Steven Low

Steven Low is the author of Overcoming Gravity: A Systematic Approach to Gymnastics and Bodyweight Strength (Second Edition), Overcoming Poor Posture, Overcoming Tendonitis, and Overcoming Gravity Advanced Programming. He is a former gymnast who has performed with and coached the exhibitional gymnastics troupe, Gymkana. Steven has a Bachelor of Science in Biochemistry from the University of Maryland College Park, and his Doctorate of Physical Therapy from the University of Maryland Baltimore. Steven is a Senior trainer for Dragon Door’s Progressive Calisthenics Certification (PCC). He has also spent thousands of hours independently researching the scientific foundations of health, fitness and nutrition and is able to provide many insights into practical care for injuries. His training is varied and intense with a focus on gymnastics, parkour, rock climbing, and sprinting. Digital copies of the books are available in the store.